— Shivam Moga —

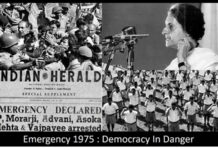

A simple line ‘kisan-mazdoor ekta zindabad’ (‘Long Live Farmer-Labourer Unity’) reverberated at the Delhi borders as one of the most popular slogans of the year-long farmers’ protest, which led Prime Minister Narendra Modi to repeal the three contentious farm laws.

The slogan contains a sense of unity and solidarity which was needed to win the fight against crony capitalism and feudal divisions. It exuded a sense of ‘social solidarity’ which was necessary to produce egalitarian social relations between farmers and agricultural labourers. It was not just a slogan which emerged in the meetings of Sanyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM) with top-down approach; rather it was envisioned by the protesters themselves in a holistic manner and that is why this slogan has no ‘feeling of imposition’, which also strengthens the organic solidarity of the toiling masses, farmers and labourers.

The slogan did not evolve in one day and from one particular social group; it was the result of a continuous process which was achieved over days. As someone who has been associated with the protest since its inception as part of the Trolley Timesteam, I have seen a positive change in the politicisation of farmers’ unions by being a part of organising this movement.

I was born in Muzaffarnagar to a family of agricultural labourers. The district is known for its history of farmers’ movement. Bharatiya Kisan Union’s (BKU) past is still fresh in the popular imagination of the people here. Mahendra Singh Tikait, affectionately called ‘Baba Tikait, co-founder of BKU and the father of BKU leader Rakesh Tikait, led many protests to advance the agendas of farmers, and before that Chaudhary Charan Singh, who also co-founded the BKU, worked towards the agenda of tackling the problems of the farmers, politically.

In the past, BKU’s rallies had slogans on ‘Kisan Ekta’ (farmers’ unity), leading to a continuous invisiblisation of the mazdoor (labourer) identity. There were many incidents of contestation between members of the BKU and Bhartiya Mazdoor Union (BMU) over minimum wages and forced labour.

The BKU’s failure in putting a ‘kisan’ and ‘mazdoor’ united front in the 1980s rendered the concerns of rural India to be allayed in the popular imagination of political consciousness of the nation for more than three decades. BMU was formed by the rural poor in response to the domination of farmers over lower classes of agriculturists.

However, in the farmers’ movement, there was a formidable change when farmers’ organisations united with agricultural labourers to win this fight. It was personally overwhelming to see the slogans changing from ‘kisan ekta’ to ‘kisan mazdoor ekta Zindabad’. For the first time in the history of the farmers’ movement, protesters were chanting slogans for Jat-Dalit bhaichara (unity). The call for social unity was also raised in the songs that were performed at the protest sites. This engendered a frame of equality across hierarchical levels of graded inequality and social stratification.

The farmers of Punjab seem to understand that this conflict cannot achieve victory without the support of all stakeholders in the agrarian political economy, more specifically the farm labourers. Today when the movement has risen victorious, the farmers’ movement emblematic of social solidarity is desired back in the villages.

The saga of social unity

When the farmers’ movement began, those from Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh were hesitant in proclaiming the slogans of ‘kisan-mazdoor ekta zindabaad’. This ideology has roots in the history of the farmers’ organisation and associations of the region.

One has to trace political attempts by leaders and unions in the region of western UP and Haryana as well as their success and failures in consolidating and mobilising the farmers’ movements since independence. If we specifically talk about the region of western Uttar Pradesh, there was no social significance or a role played by agricultural labourers in the farmers’ political decisions and movement. They were only significant whenever there was a political role for them to play as “cannon fodder”.

Charan Singh worked towards alleviating the lower classes from such a jeopardising position and achieving a base of supporters who took part in the political process, electorally. He formed the Dalit Mazdoor Kisan Party which dissolved soon after. Mahendra Tikait along with Ajit Singh formed the Bhartiya Kisan Kamgar party in 1996 before elections, but it failed at mobilising farmers and agricultural labourers electorally because the Bahujan Samaj Party constituted a majority of support through agricultural labourers’ votes.

Again, Rakesh Tikait formed a political party to contest elections in 2004; this time he named it ‘Bahujan Kisan Dal’ which was also a failed attempt because they did not have any programmes to resolve rural contestations and contradictions.

The leaders’ political actions to achieve social unity of farmers and labourers as a rising multitude against tyranny, composed of the oppressed classes, failed as they were unable to locate the concerns of the subaltern in their domain of power struggle.

This time too, it was mainly the Left parties who were mobilising agricultural labourers at the Ghazipur border (farmers mainly from West UP and Uttarakhand), which was not sufficient alone. I could see a kind of ‘neo-Dalit solidarity’ within the movement, and especially after Bhim Army chief Chandrashekhar Azad met Rakesh Tikait – who had sent out an emotional appeal on January 28 that he would rather die by suicide than end the agitation – and offered help to strengthen the protest.

After that incident I have met many Dalit youths in the National Capital Region (NCR) who used to come to Ghazipur border to show their solidarity. While talking to some of them, I could see how they considered Rakesh Tikait as their ‘Taau’ – exuding elderly respect for him.

In rural west UP, there’s a change among Dalit youths who are cognizant of a political voice preparing and mobilising themselves, albeit many of them do not engage in agricultural work but go to nearby towns where they can avail better opportunities. Such a phenomenon of migration made this solidarity possible because direct contestations with kisan is now more latent and not as evident as in the past where they were forced to work on the fields of rich farmers, and this was one of the reasons that halted this unity in the past, giving way to social discrimination based on feudal practices.

These youths are connected to Ambedkarite ideology through social media platforms. Besides, SKM’s collective decision-making that involves a larger section of the affected classes and castes also served an important purpose towards collaboration of subaltern counterpublics and these decisions proved influential in regions wherever farmers’ unions part of SKM were active.

SKM even decided to observe Ambedkar Jayanti in all the borders cordoned off as protest sites. Tikait was joined by Azad at the Ghazipur border to pay tribute to Babasaheb Ambedkar on April 14. This act sent a strong message towards the unity between Jats and Dalits, and farmers and agricultural labourers.

Another instance which was seen as a welcome step to unite Dalits and farming castes was when Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) launched the Dalit outreach programme ‘Nyay Yatra’, covering districts of western UP. This also testified to the concerted efforts of both these classes and social groups to develop close ties with each other. RLD president Jayant Chaudhury also went to Hathras to meet the family members of the Dalit woman who was gang-raped and brutalised, and succumbed to her injuries at a Delhi hospital. Chaudhury and others were lathicharged after they broke the police barricade to reach the victim’s village. The party held mahapanchayats at Muzaffarnagar and Bulandshahr on this issue.

A united front by farmers and labourers

In Punjab, there was unprecedented mobilisation of agricultural labourers from the state, all thanks to many Left-affiliated farmers’ unions, who worked towards making the farmers’ protest a collective struggle of all stakeholders in an agrarian social structure. Organisations like Zamin Prapti Sangharsh Committee, Punjab Khet Mazdoor Union, Mazdoor Mukti Morcha and Dehati Mazdoor Sabha were among those Left-affiliated organisations who work with farm labourers on issues of minimum wage, social boycott and land redistribution. Members of these organisations were regularly coming to morchas at Tikri and Singhu borders. They were less in number, not permanently part of the protests, as they feared losing their daily wages, but there was a strong mobilisation of them in Punjab at many occasions.

The ‘Kisan Mazdoor Rally’ in Barnala – jointly organised by BKU (Ekta-Ugrahan) and Punjab Khet Mazdoor Union – was such an example. The rally was attended by over two lakh farmers and agricultural labourers in a massive show of strength against the agri-marketing laws.

SKM’s decisions to celebrate events related to Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi heroes hold a different strength in building the farmers’ movement sui generis. One of the key decisions was to celebrate Guru Ravidas Jayanti at all morchas, which was attended by many farmers and Dalits. Moreover, Sikh organisations even organised a nagar kirtan at the Singhu border. Guru Ravidas has significant importance in Sikhism where his egalitarian verses are part of the Guru Granth Sahib, suggesting a historically traceable interfaith cosmology and shared idioms in sacred practices.

There were protest songs that mentioned the desired unity of ‘kisan-mazdoor’. One such song was Kanwar Grewal’s Aakhiri Faisla, which says ‘Hum banayeenge kisan-mazdoor ekta, tera chutega picha zindabaad bolke’. There were various other songs which talked about ‘kisan-mazdoor ekta’. There was a Bahujan library at the Singhu border set up by research scholars from Punjab University.

It is also appreciable and noteworthy that young generations from agrarian families are recognising the problem of “untouchability” and even coming forward to resolve it with extreme sensitivity, which was largely unheard of in the past. All credit goes to the farmers’ movement, which made them self-reflexive enough to realise their dominant position within the social order. The farmers are also mindful of the fact that without the support of a particular section, the larger fight cannot be won. Recently, a short documentary Manas ki Jaat by singer Harf Cheema gave out a social message about rural hierarchies and pointed out separate cremation grounds for Jats and Dalits in villages.

In Haryana, the movement was largely mobilised by khaps, but many farmers’ organisations were part of the protest as well. One of the main leaders from Haryana was Gurnam Singh Chaduni who talked about the importance of Babasaheb Ambedkar in the movement and urged farmers to keep Ambedkar’s photo in their homes. He also participated in a “Dalit-Backward Classes-Mazdoor-Kisan Panchayat” in Haryana’s Rohtak.

While writing this article, I was invited to the ‘Sankalp Sabha’ organised by Kisan-Mazdoor Sangharsh Sahyog Manch in Rohtak, where one of the speakers, Indrajeet Singh of All India Kisan Sabha, mentioned in his speech an interesting moment: on the day when farmers were going back to their villages, they were taking back the statue of Sir Choturam carrying a Sikh farmer on his shoulder (a symbol of Haryana-Punjab Ekta).

As they were vacating the protest sites, farmers took photos and chanted ‘Kisan ekta zindabaad’. A mazdoor, who was standing nearby, said ‘Mazdoor kadde gaya? (Where is the labourer in that slogan) and then all of them collectively chanted: ‘kisan-mazdoor ekta zindabaad!’

The larger question remains unclear: will there be real solidarity of agrarian castes in the villages? Gopal Guru in his latest editorial of the Economic and Political Weekly talks about ‘Moral Hegemony’ of farmers. He writes, “Minorities and Dalits showed their association with the protests not only because they would expect a trickle-down or positive impact on their wages in the aftermath of the success of the protest, but much more importantly, they see in such protests – driven by moral hegemony – a promise of social solidarity expressed in equal social standing against the authoritarian tendencies that are increasingly undermining democratic and constitutional principles.”

The question is, will there be a continuation of that beyond the protest spaces?

If moral hegemony won by farmers and attributed to them seems to be a novel line of thought, then we must consider it a consequence of organised efforts by both Jats and Dalits to permeate across feudal barriers. He further talks about framework for “solidarity in itself” which also needs to be extended to “solidarity for itself” standing with the long-term aspirations of social groups from the margins.’

This movement has revealed some crucial insights to see what would work out on the ground and taught us how to create the working conditions for a victorious movement. Everyone part of the protest should know that a dent in this unity will sharpen the already existing fault lines among farmers and marginalised groups, giving the actually existing capitalism a push which the ruling class will certainly take advantage of.

(Shivam Mogha is co-editor with Trolley Times, a newspaper part of the farmers’ protest. He is also pursuing his PhD in Sociology. Courtesy: The Wire.)

Discover more from समता मार्ग

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.