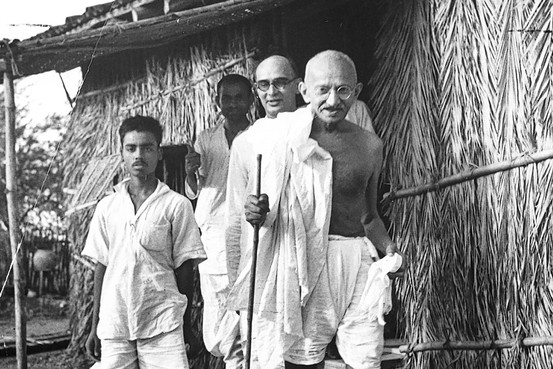

— Dr A. Raghu Kumar —

Franz Kafka said once: “There are only two things. Truth and lies. Truth is indivisible, hence it cannot recognize itself; anyone who wants to recognize it has to be a lie.” Though it appears at the outset as a complex idea, in simple terms we may reduce it to a single statement: Truth is indivisible. What Kafka said in terms of a literary expression Gandhi had practiced all through his life. His idea of Truth is also indivisible: it means you cannot have two truths, one for your private life and another for public consumption. Modernity is happy with the external truth: what is said or what is written. It cannot understand truth in terms of what one did. When he announced in and around 1929 that till then he was believing that God was Truth and he came to the conclusion that Truth is God, it was a paradigm shift in his life and philosophy. He was trying to understand what it meant by “Truth” since his early days in South Africa; he experimented on the idea of adhering to Truth (Satyagraha). But between 1927 and 1929 he had some series of discussions with Gora, the well-known atheist from Andhra Pradesh. Gora could convince Gandhi that there was a possibility of reaching through a God-less path. Gandhi later considered “TRUTH” was superior to any other pursuits including God!

There is a general presumption among many intellectuals, and especially among Marxists, Ambedkarites, some Nehruvians, socialists, and liberals that Gandhi didn’t specifically condemn “Caste” in clear terms as the others did. Some went to the extent of considering him as a Manuvadi because he claimed himself to be a “Sanatin” all through his life and recited the name of “Ram”. One of the greatest tragedies of the modern mind is that it takes written texts or spoken words seriously ignoring the actual endeavors of an individual in his life. We are failing to lift the veil of the written words and spoken texts and find the truth lying behind the smokescreen of image. Did Gandhi believe in caste? Did he believe in Varnashrama Dharma?

To understand Gandhi’s stand on caste we need to recall some instances in his life. The first one was: his being expelled from the caste by his Modh Baniya caste elders. It was when Gandhi was making his efforts to go to England for his Bar-at-Law studies. When he could somehow convince his mother by taking all the vows prescribed by her with the help of another Modh Baniya-turned-Jain monk, Becharji Swami, he encountered a last minute challenge from the caste-heads. They objected to Gandhi traveling overseas as there was a ban on such a thing in the religious texts. In the meeting held with the caste leaders Gandhi said affirmatively that “… I think the caste should not interfere in the matter.” Outraged by his discourteous remark, they declared him as “Outcaste” [M.K. Gandhi, The Story of my Experiments with Truth, Chapter – 12, p.48-50, NCBA (P) Ltd, New Delhi]. Gandhi was in his teens, and to be precise in his nineteenth year. Though after his return to India in 1891, and at the instance of his elder brother to pacify the caste-heads some rituals were performed, the caste-heads removed the barriers partially, only to the extent of some relatives from his wife’s side. Gandhi never regretted his decision nor sought for re-entry into the caste.

Gandhi in his life-time established four Ashrams to experiment his ideals – two while in South Africa – Phoenix Ashram, and Tolstoy Farm, and two while in India, – Satyagraha Ashram at Sabarmathi, and Sevagram Ashram at Wardha. He was initially inspired by a visit to a Trappist monastery near Durban in April 1895. During 1893 when he reached South Africa, he already had entertained an idea of experimenting with communal living. His idea was to live along with family, friends, workers etc. “It was the Order of Trappist Monks living at Mariam Hill near Pinetown, sixteen miles from Durban, that provided him with a functioning example of a micro-community living on the basis of voluntary poverty, self-renunciation and constructive work” [Mark Thomson, Gandhi and his Ashrams”, Popular Prakashan Pvt Ltd, Mumbai, 1993, p.42] All these Ashram experiments are classless, caste-less, voluntary societies where everyone has to do all the jobs required for the Ashramites, whether it was sweeping, cleaning, washing clothes, cooking, weaving the required cloth for the members, agriculture, shoe-making and scavenge works. There is no fixed work for anyone; everyone has to do every work without exception.

His Ashram experiments derived its sources both from the ancient India, and as well from the best community experiments of the west. He deplored the isolationist mentality characteristic of Christian asceticism, believing that “to live a pure, holy life on a pillar or in a commune is impossible, because man is deprived of one-half of life-communion with the world – without which his life has no sense.” His ashrams were social centers with a greater connectivity with the society and people. The seeds of Gandhi’s opposition to the inequities of caste were sown during his childhood, and deepened as a result of his contacts with theosophists. Though the theosophists were drawing the attention of the society to the problem of untouchability, Gandhi saw it in a much wider context as implying much more. He saw the city-dweller had come to think of the villagers as untouchable. Gandhi in his later days called on all Hindus, to regard themselves as shudras. He went to the extent of saying that by calling themselves as shudra is the only way of establishing Varnashrama Dharma. His idea of Varnashrama was not to revive the old system but put it again on its head.

Mark Thomson, in the above cited book, writes: “No caste distinctions were tolerated in the Kochrab and Sabarmathi Ashrams and every member, child and adult alike, was required to contribute to the maintenance of the Ashram and to devote a certain amount of their time each day to the constructive work.” Everyone has to do manual work, scavenging as part of day-to-day life, irrespective of their caste and religion. After the Quit India Movement he moved to Wardha making Sabarmathi ashram as a trust for the assistance of untouchables and was renamed as the Harijan Ashram.

In Wardha Ashram Gandhi encouraged local untouchables to participate in every activity of Sevagram. He arranged tanning classes where the skinners were taught improved methods and a variety methods of the use of flesh and bones of animals. He was bitterly opposed by the orthodox Hindus. He also recruited local untouchables to work with him and Sushila Nayyar, to be trained in his nursing methods. He also chose a local untouchable boy to render him personal services. He also allowed an untouchable to solemnize the wedding of a Brahmin, Dr A.G. Tedulkar, and an untouchable woman, Indumati, on 19th August 1945. [Nishikant Kolge, Gandhi against Caste, Oxford University Press, 2017, p.25]

“I am not built for academic writings. Action is my domain.” [Gandhi quoted in Iyer, The Moral and Political Thought of Mahatma Gandhi, p.10] Nishant Kolge, in his Gandhi Against Caste, cited above, writes: “Gandhi’s strategy is different from that of the Dalit anti-caste movement of his time in another aspect: he placed a great emphasis on restoring the dignity of manual labour as a means of removing caste hierarchies and differences” while “Dalit anti-caste movements aimed to achieve equality for everyone by assuring a higher status” [Nishikant Kolge, op.cit., p. 99-100]. His ideas were constructed around ‘dignity of labour’ which meant no work was a lower one and equally no work was a higher one.

In September 1915, Gandhi admitted an untouchable family, Dudabhai Malji Dafda, his wife Danibehn and their daughter Lakshmi, into his Satyagraha Ashram. The ashram’s inmates were basically members of Gandhi’s Phoenix Farm who had already lived together with the untouchable. However, once back in India the ugly face of their caste-ism raised once again. His own wife and his trusted disciple, Mangal Gandhi and his wife Santok refused the admission. All the monetary help to the Ashram stopped. Gandhi didn’t budge an inch from his stand, but learnt several lessons out of the incident. We find during these early periods he avoided writing directly against caste system, but practiced his idea at field-level. But he started becoming expressive condemning untouchability from 1920s. He wrote in 1920: “We may not cling to putrid customs and claim the pure boon of swaraj. Untouchability, I hold, is a custom, not an integral part of Hinduism. The world has advanced in thought, though it is still barbarous in action. And no religion can stand that which is not based on fundamental truths. Any glorification of error will destroy a religion as surely as disregard of a disease is bound to destroy a body.” [M.K. Gandhi, CWMG, Vo..19, p.20]. Between 1920 and 1930s he was stressing more on inter-dining and inter-caste marriages. In 1921 he appears to have said that he was against both. It was for the first and last time he gave such statements. We find serious changes in his writings somewhere around 1927-32.

From 1927 onwards he embarked upon an extensive tour to spread his messages of removal of untouchability, spinning of charkha, and Hindu-Muslim unity. It was the period of the beginnings of the Vaikom Satyagraha, the movement of the Mahars to enter temple at Amaravati, Maharashtra under the leadership G.A. Gavai. It was also the time when Babasaheb Ambedkar launched his Mahad Satyagraha. Gandhi responded to the demands of the times. Gandhi emphasized that purna swaraj would come only through the constructive work in the villages with a stress on charkha, removal of untouchability, and Hindu-Muslim unity, the three serious challenges for national unity. “For reform of Hinduism and for its real protection, removal of untouchability is the greatest thing” he wrote. M.K. Gandhi, ‘Notes’, 6 January 1927, CWMG, Vol.43, p.171]. He established the Gujarat Vidyapith and also a Committee in the Congress in the period between 1927-29.

There was a further radicalization in his thoughts between 1932 and his death in 1948. In a letter addressed to Vallabhram Vaidya on 4 December 1945, he said: “Maybe you are not acquainted with my views as they have progressed. They were of course implicit in all my writings but of late they have become more explicit. … What I believe is that if we want to preserve whatever is good in varnashrama every Hindu has to become not only a Shudra but an atishudra, and regard himself as such. And as a true indication of it marriages should really take place only between atishudra and the so-called other varnas. [Gandhi, CWMG, vol. 82, p.162].

With all these changes in the stand of Gandhi on untouchability and his continued action on his constructive programs, a real thorn that haunts the image of Gandhi as a liberator of the downtrodden is, the Poona Pact of 1932. It is not an appropriate place for dealing with the subject but Nishikant’s “Gandhi Against Caste” OUP 2017 deals with the subject matter in detail. Nishikant concludes the discussion: “Borrowing Suchitra’s expression [reference here is to a book by Suchitra Kriplani’s work “What Moves Masses”] it can be argued that Gandhi’s decision to go on fast unto death can be understood as part of his strategy to create ‘live drama’ to strike an emotional chord with the common people and prepare them for a movement that would attack the caste system.”

After this fast, Gandhi went on to arrange an inter-caste / varna marriage between his son Devadas Gandhi and Lakshmi, the daughter of Rajaji, a well-known Brahmin leader from Tamilnadu. Later he started his Harajan Yatra on 5 November 1933 and continued up to 2 August in 1934. During this period he travelled around 12,500 miles across the country. His tour itinerary included Maharashtra, the Central Provinces, Delhi, Andhra, Mysore, Malabar, Travancore, Orissa, and Bengal. What was the actual effect of this tour needs a detailed examination. This was also the time when he converted his Sabarmathi Ashram into a colony for Harijans. He later established his Sevagram at Wardha in which Harijans were part of every activity. In August and September he wrote two letters to his magazine Harijan, one on 13 August 1940 and another on 14 September 1940 where he said: “I must repeat for the thousandth time that Hinduism dies, as it will deserve to die, if untouchability lives.” [CWMG, Vol.72, p. 450 & 379.]

We may recall that in 1920s he appreciated caste and Varna as useful economic systems, but by 1934 he wrote: “Varna is determined by birth, but can be retained only by observing its obligations. One born of Brahmin parents will be called a Brahmin, but if his life fails to reveal the attributes of a Brahmin when he comes of age, he cannot be called a Brahmin. … On the other hand, one who is born not a Brahmin but reveals in his conduct the attributes of a Brahmin will be regarded as a Brahmin” [Gandhi, Introduction to “Varnavyavastha”, 23 September 1934, p.65]. In another letter addressed to Motilal Roy, on 9 November 1932 he wrote: “I have come to see now clearly, namely, that the four varnas are no longer in working order, even as the four Ashrams are not. Hence at the present moment there is only one varna in existence. We are all Shudras and if we can bring ourselves to believe this, the merger of the Harijans in Savarna Hindus becomes incredibly simple.” [CWMG, Vol.51, p.189]

Gandhi openly declared after 1934 that he would not attend any marriage if it were not an inter caste marriage. From 1945 onwards, the changes that show in Gandhi’s writings were not limited to untouchability. He said very explicitly: “The caste system as it exists today in Hinduism is an anachronism. It is one of those ugly things which will certainly hinder the growth of true religion. It must go if both Hinduism and India are to live and grow from day to day.” [M.K Gandhi, “Answers to Questions”, 16 April 1945, p.25]. He was coming much nearer to Ambedkar. Nishikant Kolge in his book “Gandhi Against Caste” writes: “… for Gandhi, the problem with the caste system was not just that it deprived one group of people, symbolically (the right to wear the sacred thread) or in real terms (political power and economic benefits), of equal status in society as the other groups. The real problem with the caste system was that it created a false consciousness of hierarchies and differences in the minds of the people. He believed that this false consciousness obstructs every individual’s path to self-autonomy.” [Nishikant Kolge, Gandhi Against Caste, OUP, 2017, p.206]

We see a progressive intensity in Gandhi’s approach towards untouchability, caste discrimination and varna system as he advances in his age and experience. But it was true there were two choices before the generation of nineteenth and twentieth century Indians – social reform or political freedom. Which should occupy the priority was a question of difficult choice. Gandhi and the Congress tilted towards the political freedom. They were of the opinion that we can resolve our domestic challenges after attaining political freedom and on our own accord without the necessity of the intervention of a foreign ruler. Dr B.R. Ambedkar consciously took the choice of social reform as the priority.

He was apprehensive of the liberality of the Hindu society. He didn’t believe that the Hindu society pursues its own reform if the compulsions of the freedom struggle were over. Both are correct in their own choices and the conflict has actually helped in quickening the dismantling of caste structures. In fact, Jawaharlal Nehru and Dr Rammanohar Lohia also made some contributions towards understanding the problem. While Nehru’s was much similar to the Marxists, i.e the understanding of caste on the basis of political economy, Dr Lohia’s has been radically different and independent. Lohia thought in terms of abolition of caste both by means of law and as well by providing affirmative socio-economic action such as reservations even beyond the eligible percentages for a certain period. All these inputs are equally necessary to revisit the problem.

It is time Gandhi and Dr B.R. Ambedkar are revisited and examined not as antagonistic forces but forces acting on a subject with different perspectives and which have great potential for synthesis. The caste is now more than the caste avocation. It is a caste of mind. The synthesis of Gandhi and Ambedkar may result in a better strategy to challenge this problem in the mental and psychological arena along with the material and physical domains of inter-caste marriage. It is more a challenge of mindset than on the economic and political arena. Political and economic power, no doubt are visible physical structures which need to be leveled, but until the caste of mind is attended to, the challenge continues to plague the Indian society, the thinking men and activists.

Discover more from समता मार्ग

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.