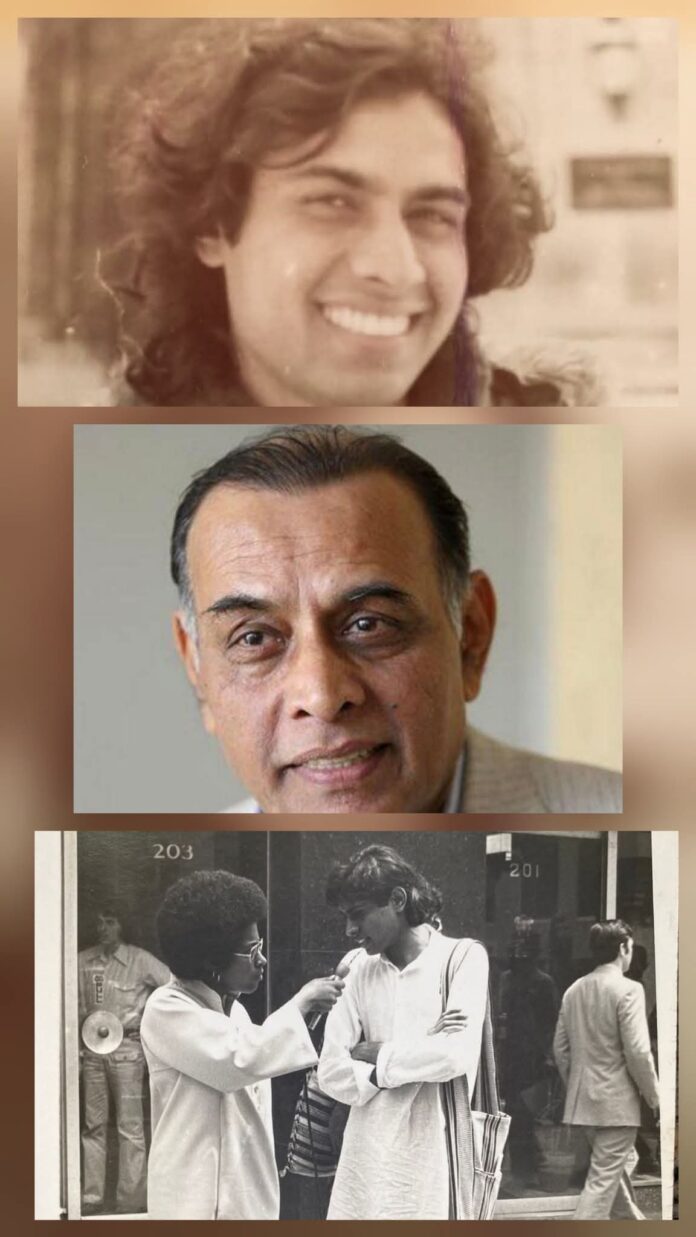

Inside the Conscience Network: Anand Kumar (PhD’86), Defending Democracy in India

by John Mark Hansen

On June 25, 1975, the President of India, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, declared a national emergency. Acting under a provision of the Indian constitution at the urging of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, he authorized her to rule by decree and suspend civil liberties. Her government muzzled the press and jailed opposition leaders. The most prominent of the imprisoned dissidents was Jayaprakash Narayan, known by all Indians as “JP,” a close associate of Mohandas K. Gandhi and the organizer of a coalition of opposition parties that ranged from the socialist left to the Hindu nationalist right. (Indira Gandhi was the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Indian prime minister, and unrelated to the Mahatma.) The world’s largest democracy passed into a phase of autocracy just twenty-five years after its constitution came into effect.

In the United States, a diverse group of Indian students, expatriates, and exiles created an organization, Indians for Democracy (IFD), to bring the pressure of Americans and the United States government on Mrs. Gandhi. The story of their campaign is told in a fascinating new book, The Conscience Network, by Sugata Srinivasaraju. One of the characters at the center of it is Anand Kumar (PhD’86). In June 1975, he was 24 years old and two quarters into the Ph.D. program in sociology at the University of Chicago.

Kumar was a native of Benares, now Varanasi, the sacred city on the Ganges River. He arrived at the University with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in sociology from Banaras Hindu University (BHU) and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). The University of Chicago was well known in India for its humanities and social sciences scholarship in South Asian studies. It attracted many Indian students. Like every other sociology graduate student, however, Kumar chose Chicago because its sociology faculty was the outstanding department in its field. A fellowship from the Indian government made it possible.

Kumar’s political commitments, a “mingling of Gandhian and socialist ideals,” were an inheritance. “In my family,” he told Srinivasaraju, naming four leaders in socialist and anti-colonial politics in India, “[Ram Manohar] Lohia and JP [Narayan] were heroes, Narendra Deva was a role model, and [Mahatma] Gandhi was the patron saint.” He served on the executive committee of the Young Socialists League of India. He was elected president of his university’s student union twice, once at BHU, once at JNU.

While Kumar was attending JNU, student protests against Indira-aligned state governments in Gujarat and Bihar grew into a nationwide challenge to her regime. It became known as the “JP Movement” and the “Sampoorna Kranti Movement” after its leader, JP Narayan, and his call for sampoorna kranti, “total revolution.” In March 1974, after police killed three student demonstrators at Patna University in Bihar, Kumar and other JNU students staged a protest at the prime minister’s residence. A few weeks later, he met with JP Narayan. “I was so overwhelmed,” he recalled, “that I decided to become a 100 percent unpaid servant of JP.”

Kumar was no sooner settled into grad student life at Chicago, therefore, than he was drawn into the beginnings of Indians for Democracy. In January, a JNU friend, a student at Michigan State, invited him to speak to the Indian community there about the political situation at home. After his presentation, he dined with Shrikumar Poddar. He had come to MSU in the fifties to study engineering and since had founded Education Subscription Service, which pioneered the marketing of magazines to students with flyers inserted in college bookstore shopping bags. With his wealth and expertise, he raised funds for causes in South Asia and built relationships with American politicians. Kumar stayed an extra day in Lansing to coauthor a statement on the gathering crisis in India.

He returned to Chicago with the name of another contact, Poddar’s “dynamic friend,” Sangayya Rachayya “SR” Hiremath. He had moved from India in the late sixties to study operations research at Kansas State. His first job, with the Container Corporation of America, brought him to Chicago. At a dinner party in Hyde Park, he met Mavis Sigwalt (AM’71), a student at the School of Social Service Administration. They married and settled in Downers Grove.

Kumar met Hiremath shortly after his return from Michigan. He was also an admirer of JP Narayan and concerned about the direction of Indian politics. Within days, the operations expert drew up a plan for mobilizing support for the JP Movement in America. The first step was creating an organization, the second, sending Kumar on a national lecture tour to promote its cause to students and the diaspora. The name the organizers chose, Indians for Democracy, echoed “Citizens for Democracy,” an organization Narayan started in India. Drawing from his speeches, Kumar wrote a three-page letter to the Indian community to raise awareness and rally support, posting them from his apartment at 850 E. 57th Street, #9.

His tour began in April, twenty-two cities in ten weeks. He tended to his classes during the week and traveled on weekends. As urgent as the situation appeared, the Emergency was not yet in prospect. Kumar, Poddar, Hiremath, Sigwalt, and the other IFD founders imagined that “JP’s moral standing would tame Indira Gandhi’s arrogance…. Their effort was to build a pressure group in the United States to influence the trajectory of reform and development in India” afterwards. Like JP Narayan, Indians for Democracy welcomed support from across the political spectrum.

All this while, Kumar was a University of Chicago doctoral student, attending seminars, taking exams, and writing papers in sociology. In his first quarter, guided by his advisor, China expert William Parrish, he took classes on social stratification, political sociology, social analysis, and social mobility. Later, he studied other topics, including macrosociology, revolutions, political development, and modernity in India. He was active in a project on the comparative study of new nations. “I was very focused on the courses,” he told me. “I made the Regenstein Library my second home.”

On June 12, 1975, as Kumar’s tour neared its end, a justice of the Allahabad High Court ruled that Indira Gandhi illegally used government resources to win reelection in 1971 in her constituency in Uttar Pradesh. He voided the election and ordered her removed from her seat in the Lok Sabha and her office as prime minister. She vowed to resist. Her supporters and opponents took to the streets. Twelve days later, a justice of the Supreme Court upheld the decision. The next evening, near midnight, her ally, President Ahmed, granted her demand for extraordinary powers. Hours later, police arrested JP Narayan at his quarters in Delhi. The Emergency began.

Kumar heard the news in New York City. He was scheduled to speak at Columbia along with other IFD leaders. They recognized the moment for what it was: a requisite and an opening for broader action. Indians for Democracy staged a protest at the Indian Embassy in Washington four days later. They constituted a six-member steering committee, Kumar among them. Then they sent him back on the road.

In July and August, he made three dozen appearances in eighteen cities. Now his lectures got more attention. He spoke at Washington University in St. Louis, predicting that “a crush of popular opinion [will] bring the government down in six months.” In the following weeks, he was in Iowa City, San Francisco and Berkeley, back in Iowa City, then Madison. He articulated the demands of the JP Movement in India: “the lifting of the state of emergency; an immediate release of all political prisoners; a restoration of the fundamental rights of all Indian citizens including freedom of the press; and allowing the judicial process to continue in seeing that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi abides by the ruling of the Supreme Court of India.” In October, with the University back in session, he addressed “The Political Crisis in India” at the Crossroads International Student Center on Blackstone Avenue.

The coverage of the Emergency in the American press brought the cause of Indians for Democracy to the attention of a public beyond college students and the Indian diaspora, appealing to Americans who admired Mahatma Gandhi and his tenets of nonviolent resistance to oppression and Americans dedicated to democracy and human rights. In Madison, Kumar and Hiremath met Wisconsin professors who put them in touch with activist friends of like mind.

At MIT, they visited the radical linguist Noam Chomsky, who shared a letter of protest he had just addressed to Indira Gandhi. Others approached John Kenneth Galbraith, a Harvard professor and President Kennedy’s ambassador to India.

In January 1976, the IFD and allied groups chartered the Committee for Freedom in India, a federation “concerned [with] the decline of democracy and the erosion of human rights in India since 26 June 1975.” The Rev. G. G. Grant, a Jesuit priest and Loyola professor, was the chairman and SR Hiremath was the executive secretary. Mavis Sigwalt and Anand Kumar represented Indians for Democracy. The committee included others with ties to the University of Chicago: C. M. Naim, a professor in South Asian Languages and Civilizations; law student Alex Spinrad (JD’76), the new Student Government president; and Hyde Parker Bradford Lyttle, the son of a professor at the Meadville Seminary and an on-and-off student in the University. Father Grant sent Kumar and Hiremath on another mission to solicit support from American opinion leaders.

On a cold February morning in 1976, Kumar received a telephone call from the education secretary in the Indian Embassy. The man inquired whether he had been on “some kind of lecture tour.” Receiving confirmation that he had, the secretary asked whether Kumar’s scholarship from the Indian government was to enable him to study or to go around giving lectures. Kumar replied that he traveled on weekends and met all his classes during the week. In the autumn quarter, in fact, he had passed his prelim and, recently, the first of two special field exams. The answer, however, was not to the secretary’s point. “You are not supposed to criticize the Indian government on foreign soil,” he said. “The ambassador is very unhappy.” A few days later, an official in the Chicago consulate told Kumar that his fellowship was canceled and he should arrange his return home.

Kumar’s response was wryly defiant. “I feel quite satisfied that the government of India has now taken notice of my activities,” he told a New York Times writer. “Otherwise I was really frustrated that we were doing so many things and nobody is taking any notice. So it’s kind of gratifying to me personally.” The article, a discussion of the actions of the government and the protests of Indians in the United States, began on page one and continued for more than half a page inside. Several newspapers reprinted it. Hundreds more published Kumar’s mordant riposte.

The Chicago Tribune also condemned the retribution against him. It noted the Indian ambassador’s remark accusing Indians for Democracy of “degrading themselves by washing dirty linen in public.” “But who dirtied the linen in the first place?” it asked. “According to our national values, [the ambassador] would serve his country better by advising the government in New Delhi to cease giving offense than by criticizing Indian nationals … who take offense when serious offense is given.”

The University of Chicago community rallied to Kumar’s support. The social sciences dean of students, Kenneth J. Rehage (AM’35, PhD’48), wrote to the ambassador, the education minister, and the president of India. “Mr. Kumar has an excellent record as a scholar in the field of Sociology at the University of Chicago,” he testified. “The Division of the Social Sciences, as well as the Department of Sociology, will regard it as a great misfortune if he is unable to continue his studies with us.”

The Indian Students Association organized the Ad Hoc Committee for the Defense of Anand Kumar, which agitated for his relief. (They shortly turned it into the International Students Defense Committee, supporting colleagues subject to despotic regimes in other countries too, naming Chile, Argentina, Iran, Ethiopia, Greece, and Taiwan in addition to India.) Student Government got involved. Many sympathetic professors, notably Bernard S. Cohn and Milton B. Singer (PhD’50), anthropologists and India experts, urged action as well.

The pleas to the Indian government were for naught. The Social Sciences Division absorbed Kumar’s tuition, enabling him to maintain enrollment and retain his student visa. For his subsistence, he relied on donations from admirers and friends, twenty hours a week in the Tribune mail room, and, finally, a job as a guard in Regenstein and D’Angelo.

Kumar pursued the IFD campaign to restore democracy to the end. He undertook a third speaking tour in 1976, appearing in fifteen cities and campuses. He helped with demonstrations in New York, Chicago, and Washington. In September 1976, he took part in a 120-mile trek from Independence Hall in Philadelphia to the United Nations in New York, a “Satyagraha March” meant to evoke the ideals of the American Revolution, the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and Gandhi’s great movement for Indian independence.

Mrs. Gandhi finally announced the end of the Emergency in January 1977. In eighteen months, she believed, she had succeeded by imposing “order” in “revers[ing] the political deterioration” that prompted her to declare it, Chicago political scientists Lloyd I. Rudolph and Susanne Hoeber Rudolph wrote. “Although the crest of the wave of political gains from the emergency had broken, the political tide appeared still to be high. Before it receded, it seemed expedient to capitalize on the apparently favorable environment.” She called elections for March and set the Emergency to expire just after.

She miscalculated. The elections were a disaster for her and her party, the Indian National Congress (INC). JP Narayan’s opposition coalition, the Janata (“People’s”) Party and its allies, won a supermajority. Her rival, Morarji Desai, became the first prime minister of India who was not from the INC. The opposition routed the Congress in the belt of northern states from Gujarat to West Bengal, the heart of the JP Movement. It lost every seat it held in Uttar Pradesh, including Mrs. Gandhi’s own. The Desai government restored Kumar’s scholarship in April 1977.

Anand Kumar departed Chicago at the end of that year. Despite the intensity of his involvement in Indians for Democracy, he had kept up his studies and advanced to Ph.D. candidacy. His dissertation committee, William Julius Wilson (the chair), Richard P. Taub, and Bernard S. Cohn, approved his proposal to study the “Political Sociology of Peripheral Capitalism: Case of India (1917–1974).” He returned to India in 1978 after a time at SUNY–Binghamton learning world-systems theory from Immanuel Wallerstein. He joined the faculty at his first alma mater, Banaras Hindu University, and moved in 1990 to his second, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Lloyd and Susanne Rudolph arranged an eighteen-month residency at the University that enabled him to complete his degree in 1986. Among the “friends and elders” he thanked in his acknowledgements were SR and Mavis Hiremath and Shrikumar Poddar.

Through rare victories and many disappointments, Kumar kept up the good fight for India’s democracy, as he saw it. In 2014, at 63, he stood for public office for the first time, slated for a parliamentary seat in Delhi by the Aam Aadni Party, which, like the JP coalition, developed from a movement opposing the corruption of a Congress Party government. He outpolled the Congress incumbent but lost to the nominee of the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Anand Kumar, his associates, and his friends and supporters at the University of Chicago wrought a compelling example of human agency in trying times. It has a sobering resonance in our own moment, on both sides of the globe.

The Conscience Lobby: A Chronicle of Resistance to a Dictatorship, by Sugata Srinivasaraju, Penguin Random House India, 2025.

John Mark Hansen is the Charles L. Hutchinson Distinguished Service Professor in Political Science and the College. He was the interim director of the University’s Center in Delhi from 2016 to 2017.

Discover more from समता मार्ग

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.